England’s first World Cup adventure was a voyage of the damned | Neil Duncanson | Football

Roll back 70 years to a grey, austere postwar Britain, still in ruins, still enduring food rationing, queues and misery, a nation where football provided a scarce escape. It was also when, for the first time, England took part in the game’s major global tournament, the World Cup, which began on 19 June 1950 in Brazil.

To hyperbole stirred up by the national prints, England were presented as certain to be returning home triumphantly from South America with the Jules Rimet trophy. Failure was never considered. Here, after all, was the greatest assembly of footballing talent ever to leave England’s shores: Matthews, Finney, Mannion, Mortensen, Wright and Milburn, a confection of Boy’s Own heroes. It was, after all, England’s game.

England, after snootily withdrawing from Fifa in 1928, had snubbed the first three World Cups and some of the press even criticised the FA for sending a team in 1950. Hubris reigned. Even the Brazilians called England the “kings of football”.

What followed, however, was calamitous. England’s first World Cup adventure was to prove an abject failure, featuring comical organisation, archaic team selection, ill-prepared training and tactics and, of course, dreadful performances on the pitch.

The early signals were ominous. Before flying to Brazil, the FA had deemed it too costly to leave early for the players to acclimatise to the high temperatures and humidity of South America. A kick-about in an empty Wembley Stadium was followed by three days of training at Dog Kennel Hill, the home of Dulwich Hamlet, where they were not allowed to use the first-team pitch because it was being reseeded.

Panair flight 261 to Rio de Janeiro, a big four-propeller Lockheed Constellation, would take the England party on a back-stiffening 31-hour journey that stopped off in Paris, Lisbon, Dakar, Recife and, finally, Rio. The party included 17 of the 20-man squad of players, the manager, Walter Winterbottom, the trainers Bill Ridding and Jimmy Trotter, four referees and eight reporters.

Missing were Stanley Matthews, who had bizarrely been sent instead on a Football Association goodwill tour to Canada, and Manchester United’s John Aston and Harry Cockburn, who were playing on the club’s tour in the United States. They would all have to play catch-up in Brazil. Also missing were the FA president, Stanley Rous, and chairman, Arthur Drewry, who arrived earlier and stayed in a different (and better class) hotel in the city.

Tom Finney almost did not make it into Brazil at all. England’s leading goalscorer lost his health certificate and after a fruitless search of the plane had to beg the Brazilian officials to let him into the country.

When the team finally fought their way out of Rio airport, with the captain, Billy Wright, comparing the escape with a scene from a Marx Brothers movie, the squad scrambled aboard the coach and drove to the Luxor Hotel, on the Avenida Atlantica, the busy main road that runs along Copacabana Beach.

The players were banned from visiting the beach during the day, for fear of getting sunstroke, and the heavy traffic and the firecrackers set off throughout the night by fans made it virtually impossible to sleep. “It was like Hyde Park Corner at four o’clock on a Friday afternoon,” one player recalled.

Built in 1917, the Luxor was a cheap, 10-storey edifice facing the ocean. It lacked air conditioning (the daytime temperature rarely dipped below 80F, 27C) and, while the players were used to sharing rooms, the catering was a disaster. Nobody at the FA had bothered to visit the hotel in advance, so it fell to Winterbottom to intercede.

Years later he remembered feeling “physically sick” when he inspected the kitchens and had to lay down a new set of rules for the chefs to follow. “All the food was being cooked in reams of black oil and garlic,” he recalled, “and the smell of it was dreadful and carried all through the hotel. Nearly all the players went down with tummy upsets at one time or another.”

“The food was terrible,” recalled Finney. “I remember the cold ham and fried eggs swimming in black oil. We were eating bananas, mostly.” Stan Mortensen put it more bluntly: “Even the dustbins had ulcers.”

Alf Ramsey, then a full-back but who would go on to have a rather more significant impact on England’s World Cup fortunes 16 years later, recalled: “We were told we should have everything ‘English’ that we required. In truth, it didn’t work out that way. But Walter quickly got weaving and, after talking to the chefs, he explained just how he wanted them to prepare and cook our food.”

England’s poor planning was in stark contrast to the hosts’ preparations. Brazil’s manager, Flávio Costa, had attended England’s game with Scotland earlier in the year and marvelled at their strength, speed and power. He saw England as their strongest rivals and showed his players films of all their recent games. He was taking no chances. The team had been closeted in a mansion in the Rio suburbs for four months, with an almost monastic regime of rigorous training, strict nutrition, 10pm curfews and no women, not even a visit from their wives.

It was said that Costa was being paid the equivalent of £1,000 a month by the Brazilian FA, with a huge bonus promised if they won the tournament. By contrast, Winterbottom, a former Oldham school teacher, was earning a little over £1,000 a year.

England had avoided Brazil in the group stages, despite Fifa failing to seed the teams. In Group B with England were the USA, Spain and Chile and, rather than going on to a knockout stage as at subsequent World Cups, the winners of each group advanced to a final-four round-robin.

Once in Rio, the England squad trained each morning and evening at the local club Botafogo, where every session was open to the public and drew crowds of autograph hunters.

Newcastle’s Jackie Milburn remembered the first morning of training. “Walter Winterbottom came and started talking to the press. He left us with three bags of balls. Normally when a bag of balls is left with a football team you’re lucky if you can get one. Everybody wants one, two, three of his own if he can possibly get them. But the whole bunch of us played cricket. What I’m trying to say is once the season is finished it doesn’t matter how willing you are, there’s nothing left.”

Missing from those early sessions was Matthews. At 35 it was widely thought the Blackpool wizard’s best days were behind him and he had not played for the national side for a year (though he would play for his country until 1957). The job of picking the team in Rio effectively fell to one man, the FA chairman Drewry, who ran a fish business in Grimsby and had been chairman of the local football club between the wars.

Winterbottom had little say in the matter. But Drewry could not ignore the clamour in the press for Matthews’s inclusion after he excelled in Canada, and he duly received a telegram in Toronto instructing him to fly to Brazil. Matthews recalled: “It wasn’t ideal preparation. The journey took us through New York and Trinidad before we arrived in Brazil after a tiring 28 hours with only three days to go before England’s curtain-raiser against Chile.”

On arrival, Matthews’s assessment of England was withering. “I was made to realise how seriously the FA were taking the World Cup. Just one England selector, Arthur Drewry, had accompanied the squad and I believe he made the journey only because he wanted to exert his influence on team selection, which he invariably did.”

Besides Matthews, England had lost their postwar old guard, with the goalkeeper Frank Swift, the captain George Hardwick, the defender Laurie Scott, the midfielder Raich Carter and the centre-forward Tommy Lawton all retired or injured. Also missing from the trip was England’s only world-class defender, Stoke’s Neil Franklin, who had been banned from playing in England for a year after he decamped to Colombia to chase a lucrative £170-a-week contract. Predictably the money failed to materialise and after pocketing just one week’s wages he returned home early when his homesick and pregnant wife, Vera, refused to stay any longer.

Although it was Franklin himself who had turned down selection for the World Cup, England never recovered from the loss of a player described by Matthews as “the greatest centre-half I ever had the privilege of playing with”.

The FA would pay each player £20 per game, plus £2 a day expenses in Brazil. Even the referees earned £70 a week. The Sunderland defender Willie Watson was persuaded to give up a lucrative summer playing cricket for Yorkshire (he went on to play for England) to join the World Cup party. He would have earned more than £300 with the bat but fared less well with the ball.

“On my return from Rio,” he later said, “I received a cheque for £60 from the FA, being my fee for the trip – I didn’t play in any of the three games – and included in the letter was a note saying that I had overcharged my expenses by 16 shillings and three pence. I don’t think I have ever been so hopping mad.”

There were lighter moments, including a lucky escape for Stan Mortensen. On an evening stroll by the beach with some of his teammates in the darkness, he suddenly fell down a huge hole in the mosaic-covered pavement that had been left behind from a tree removal. Embarrassed but unhurt, Mortensen climbed out, to the amusement of teammates.

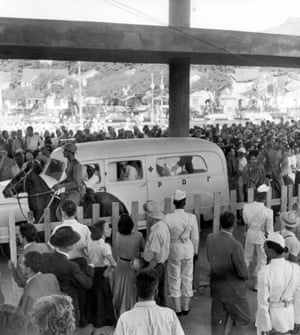

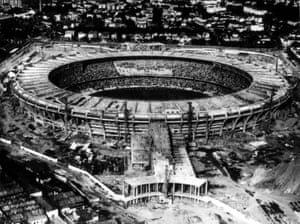

The day before England’s first game, they watched the tournament opener between Brazil and Mexico at the newly constructed Maracanã. The traffic was so bad the players got off the bus after a two-hour journey and walked the rest of the way, scrambling over rubble, barbed wire and wet concrete, their police escort swallowed up by a sea of fans, trams, buses and limousines as nearly 200,000 crammed into the giant concrete arena.

After the fireworks, balloons and a 21-gun salute, England marvelled at the fluidity, speed, skill and ball control of the Brazilians as they crushed Mexico 4-0. Clearly, the hosts would be the team to beat, as Matthews recalled: “I had seen Brazil in action and as I had been told they were the chief danger to England, I tried to pick out their weaknesses.

“They were good footballers, but they seemed to have to put too much effort into beating this weak Mexican team. I could see gaps down the middle and should we meet them I thought Stan Mortensen would have a field day galloping through those open spaces. At the end of the match I was convinced England would win the World Cup if Brazil was our chief danger.”

The following morning, after their usual pre-match meal of boiled fish, tea and toast, the team to face Chile was announced and the only real surprise, aside from Matthews’s omission, was a debutant at centre-half in place of the absent Franklin: Liverpool’s Laurie Hughes.

Chile were composed largely of part-timers, with the exception of Newcastle’s George Robledo, but they did not have to work too hard to counter England’s lethargic first-half display. But in the second half, with rain pouring down, England raced to victory, with goals from Mortensen and Mannion giving them a 2-0 win. Only 30,000 watched at the Maracanã, and every England pass was roundly booed. Still, the mood surrounding England remained upbeat.

The News Chronicle’s Charles Buchan reported: “On their display in the second half at any rate, England can win this trophy. I have no doubt now that they will beat Spain and the USA and win the group championship. This was as good an England team as I’ve seen for a very long time.”

In the other group game, the rank outsiders from the USA took the lead against Spain before tiring and losing 3-1 in the final 10 minutes. But if this defiant performance by the Americans sounded an alarm bell, it was clearly not heard by England.

Every England player, while relieved at beating Chile, complained about the heat and humidity, with oxygen being made available at half-time and full time. But it was clear that the team were running on empty well before the final whistle.

Billy Wright described finding it difficult to breathe after 45 minutes. “After running about in a match at home I take a deep breath and fill my lungs. In Rio when I did this nothing seemed to happen and although oxygen was available for us to take at half-time – we gave it a test but found it of little use – I appreciated that these were the kind of conditions we had to expect and overcome if the World Cup was to be won.”

Roy Bentley’s verdict on England’s display was damning. “Unfortunately there were no tactics or gameplan at all, and my roving game quite understandably passed my teammates by, who really didn’t know how to play to my strengths. Walter congratulated us on our performance but said ominously that we could play a lot better. As we found out a week later, we could also play a hell of a lot worse.”

England had three days to overcome their weariness before the game that would go down as arguably the nation’s greatest footballing humiliation. The match against the 500-1 outsiders would be played at Belo Horizonte, almost 300 miles north of Rio, which meant a short flight on a couple of Dakotas and a rollercoaster coach ride around some of the most daunting mountain passes and vertigo-inducing hairpins the country could offer.

Winterbottom’s squad were based in Morro Velho, the HQ of the British John d’el Rey Mining Company, an English-style community based in the mountains, which boasted first-class hotel facilities and, in a forest clearing, a football pitch far better than any the team would play on at the World Cup.

All the camp talk was not about how to defeat the USA, but how many goals would be scored. The press called for Matthews to start, but Drewry was adamant he would not change a winning team, no matter the opposition.

The USA side, managed by Bill Jeffrey, included a fellow Scot given a free transfer by Wrexham; a Haitian centre-forward; a Belgian left-back, a Pole who had played for Dynamo Moscow; and a baseball catcher in goal. While organised and spirited, Finney reckoned they would struggle to beat a Third Division team.

The Belo Horizonte pitch was bumpy, the grass matted, but England decided not to practise on it and stayed in their retreat until match day. About 10,000 fans made it to the compact stadium and because there were no adequate changing facilities, the England players were already in their kit on the bus. And for the first time in their history, to avoid a colour clash with the USA, England would wear blue.

They laid siege to the American goal, hitting the woodwork 11 times and had more than 90% possession – goalline clearances, impossible ricochets, disallowed goals, blatant penalty claims, last-ditch tackles, and miraculous saves. But, unthinkably, USA took the lead eight minutes before half-time when a speculative 25-yarder hit Joe Gaetjens square in the face and in past a mortified and wrong-footed Bert Williams. If a meteor had struck, it would not have been more unexpected.

At half-time Winterbottom told his players to relax, goals would follow. But as the second half wore on England became ever more nervous. The USA defended like demons and by the time the final whistle blew, England sensed they could have played for the rest of the day and still not scored.

The Brazilian crowd waved white handkerchiefs to signal England’s meek surrender, while Gaetjens was chaired off the pitch. Having watched from the stands, Matthews observed: “Very reluctantly I left my seat and made my way to the England dressing room. I wouldn’t like to describe what I met there, so I will draw a veil over it. It was a disaster. If we’d played for 24 hours we wouldn’t have scored. It was one of those days.”

When the reports were cabled back to Britain, most newspapers thought there had been a misprint and the score should read 1-10 – not 1-0. In the US, the New York Times dismissed the wire reports as a hoax.

Buchan, who managed to file a crackly seven-minute radio report after the game, described how the English journalists had to telephone their reports from Belo Horizonte to Rio because there were no cable facilities at the ground. “With only two telephone lines between all the reporters present there was a big delay. By the time the last message went through the pitch was in darkness. When no one could find an electric torch there was the strange spectacle of half a dozen reporters grouped around the phones in a deserted ground frantically making bonfires of newspapers so that the copy could be read to the cable office in Rio and thence transmitted to faraway Fleet Street.”

When the news eventually reached England, the reaction was incredulous. “Unbelievable Defeat Of England’s Footballer’s By USA,” cried the Nottingham Evening Post, detailing the second sporting blow of the day after England’s cricketers had suffered a 326-run defeat by West Indies at Lord’s. John Macadam wrote gloomily in the Daily Express: “United States footballers – who ever heard of them – beat England 1-0 in the World Cup series today. It marks the lowest ever for British sport.”

Winterbottom, while conceding his team had missed a catalogue of chances, was incandescent with the standard of refereeing. “We scored a perfectly good equaliser but it wasn’t allowed,” he complained. “The crowd was jeering that decision, the man handled the ball in his own net. But after that the Americans thought they could get away with anything, shirt-tugging, fouls and everything. The refereeing was a farce. If Fifa had wanted to, they could have suspended the referee for a lifetime.”

Roy Bentley found it an effort to play at his best and suffered from breathing difficulties and stomach problems, but he refused to make excuses. “From the general standard of play I guess the other chaps were not finding it easy either. But I still couldn’t believe we’d lost to the USA. The whole thing was out of perspective. It was like Babe Ruth had scored a century at Lord’s with a baseball bat.”

Billy Wright conceded: “We had no alibis for our defeat; though the pitch itself was bad, it was the same for the Americans as it was for us. To their credit the United States team played well. But I still hold that if our forwards had taken but half of their scoring chances, we would have coasted home.”

Rous, in his autobiography, Football Worlds, was unequivocal. “Stanley Matthews seemed to me to be the ideal man to undermine a team like theirs, which was clearly long on spirit and short on skill. Special arrangements had been made for him to join the party and it seemed sense to put him in for this game. That I thought also to be the view of team manager Walter Winterbottom, so I went to see Drewry to urge some changes, and especially Matthews’ inclusion. Drewry was adamant, however, that we should not change the team that had beaten Chile 2-0.”

Despite the debacle all was not lost. The final group game, back in Rio, was against Spain and victory would still take England through to the final-stage round-robin. This time, Drewry rang the changes. Out went Mannion, Aston, Mullen and Bentley and in came Tottenham’s Eddie Baily, Blackburn’s Bill Eckersley, Milburn and, of course, Matthews.

Still, England again failed to score and were beaten 1-0 by a physical Spanish side in front of 80,000 at the Maracanã. Milburn had what looked like a perfectly good goal ruled out for a dubious offside but England were out of the World Cup.

The Daily Herald crystallised England’s miserable experience in one wry notice, echoing the famous notice published in the Sporting Times in 1882, which inspired the creation of cricket’s Ashes. The updated version read: “In affectionate remembrance of English Football which died in Rio on 2 July, 1950. Duly lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances. RIP. NB: The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Spain.”

Within hours of their second defeat, the England party found themselves back at Rio airport for the long journey home, only to learn that their flight had been delayed for 24 hours. They had opted not to stay and watch the rest of the tournament, in whose final match, between Brazil and Uruguay, the hosts, despite being clear favourites, lost to their tiny neighbours 2-1.

Matthews, for one, believed it was an opportunity missed: “I felt much could be learned from them. Tom Finney quite fancied the idea [of staying on] as well but we were tied to travelling home with the England party. It is one thing for the players to return home, but neither Arthur Drewry nor Walter Winterbottom stayed on to study how the teams who had reached the next stage were applying themselves to the tournament.

“All the English sports journalists were recalled by their newspapers, so while the game of football continued to develop with new ideas being put into practice, we all went home and, to all intents and purposes, buried our heads in the sand.”

Finney could also see that football was changing. “It gave us an insight into how good the South Americans were. They were very skilful players and it was obvious you had little or no chance of playing against those sides then. We were by no means the best in the world. That was not true at all. The only reason you were probably thinking that was because you never played these sides; never saw anything about them because they were so far away.”

Winterbottom conceded: “When you look back now, you think we were innocent victims of our own lack of preparation. There was no pre-planning, no going out to look at facilities. Nothing like that. We just thought we could turn up and play. In some respects, we were a good side, but we weren’t a good enough side to win regardless on these special occasions and in such circumstances.”