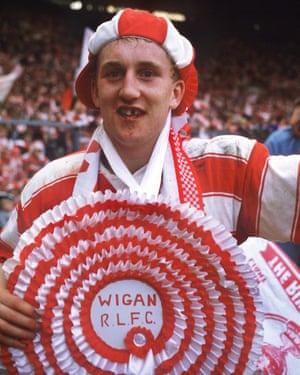

My favourite game: Wigan-Hull, Challenge Cup final 1985 | Paul Wilson | Sport

Back when the earth was young the rugby league season would be played out on an assortment of northern mud heaps in winter before the Challenge Cup final brought a ceremonial climax in early May. The sun always seemed to shine at Wembley, the two finalists generally rose to the challenge of presenting the game in its best light given space and a billiard table surface, and the happy memories would last all summer until it was time to visit places such as Odsal and Wilderspool again.

The 1985 final between Hull and Wigan certainly delivered on happy memories. Frank Keating on these very pages described it as the most voluptuous exhibition of running rugby he had ever witnessed. Note: not rugby league. He just said rugby. It was the 50th final staged at Wembley, and a procession on the pitch before kick-off featured players or representatives from each winning side down the years. All the old-timers agreed afterwards that the final was one of the most exciting and memorable contests the sport had produced.

Wigan won, though another five minutes and Hull’s magnificent fightback might have secured victory. The peerless Wigan stand-off Brett Kenny was a deserving Lance Todd trophy winner as man of the match – though, had the votes been counted at the end of the game rather than 15 minutes before its conclusion, his equally deserving Parramatta and Australia teammate Peter Sterling would have been in with a shout.

Sterling led the Hull comeback, Kenny was the inspiration behind most of the spectacular tries that propelled Wigan towards taking a seemingly commanding 28-12 lead. The pair had made their names in this country three years earlier as half-back partners for the invincible Kangaroo tourists, now they had been eagerly snapped up on short contracts by adventurous English clubs keen to import their dazzling brand of youth and vigour.

It could be argued the 1985 final was merely the first to be thus enlivened after the relaxing of an international transfer ban a couple of years earlier, though few occasions in the era of free movement since have managed to be as colourful or pulsating. Nor was the Kenny-Sterling rivalry the only thing to admire.

On one Wigan wing was the incredible John Ferguson, a hitherto unknown Indigenous Australian whose prodigious talent was only recognised by international selectors in his homeland after the two typically improbable tries he scored at Wembley. On the other was Henderson Gill, a muscular and elusive runner from Huddersfield who had endured a miserable time in the final defeat by Widnes the previous year.

For this was not the Wigan who would sweep all before them a few years later, winning the Challenge Cup eight years on the trot. Far from it, at this point in their history Wigan had not won at Wembley since 1965, when Billy Boston and Brian McTigue were still playing. Hull, with a young Garry Schofield and Lee Crooks in their side, were considered narrow favourites beforehand, although keeping Schofield under wraps until the second half was probably a mistake.

Gill scored arguably the try of the afternoon, hurtling half the length of the left touchline before lighting up the stadium with a radiant grin, though Kenny’s exquisitely controlled glide for his first-half score was just as stunning. The goal-kicking was poor throughout, indeed some Hull supporters still claim the final was lost for want of a specialist kicker, though it is also true that Wigan forced Hull out wide for their tries and were never opened up through the middle as was the case when Shaun Edwards scored.

While neither he nor his teammate Mike Ford would have had any inkling that their futures lay in rugby union, the most decorated player in rugby league history will always have a soft spot for 1985. Of the record 37 medals Edwards amassed, this was the first.