Gianluca Vialli: ‘Now I realise that whenever I want to cry, I cry’ | Football

“You feel that you are letting someone down, like your parents,” Gianluca Vialli says as his memories of cancer return with renewed force. His voice is grainy with hurt and, even on Skype, his eyes glisten. “You don’t want your parents to see you in a lot of pain.”

The former Italy striker, who also managed Chelsea, pauses because the tears have choked him. Vialli is at his home in Chelsea, where he is in lockdown with his wife and two teenage daughters. His elderly parents live in Cremona, the town in northern Italy which has been hit so hard by the coronavirus. He cannot talk as he remembers why he did not tell them when he was first diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2017.

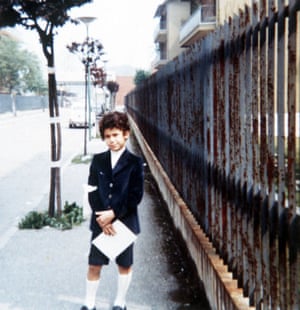

I break the silence because it’s understandable he would not wish his parents to suffer. “Yes,” the 55-year-old agrees as he composes himself. “There is also all this shame. I’ve always been perceived as a tough guy. A strong guy with a lot of determination. To not be in that position made me uneasy. I didn’t want to be looked at as a poor guy with a disease. That’s why I didn’t share it widely for 12 months.

“It’s also a burden. People will call to show they’re thinking about you. I thought that, instead of spending time on the phone, I needed time for myself. That’s why I wore a jumper under the shirt – to hide that I’d lost so much weight. These feelings are natural and stay with you a while. And then, at least in my case, they go away. The day you start looking at things differently, your life changes. Now I show my scars with pride. They are a sign of what I’ve been through.”

Vialli played 59 matches for Italy. He helped Sampdoria win the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1990 and their first Serie A title a year later. He lifted another Scudetto and the Champions League with Juventus. That 1996 final was his last game before he became a Chelsea player and then their manager during his four years at Stamford Bridge.

He has always been amiable and intelligent but, over the course of a 70-minute conversation, Vialli emerges as an even more impressive man. “I know now that you need to let out the pain,” he says. “I wasn’t particularly good at showing my emotions and I kept things inside. It’s not good. Now I realise that whenever I want to cry, I cry. There’s no shame. And if you want to laugh, you laugh. I try not to cry in front of people that might get very emotional. I try to cry by myself. When I’m in a comfortable place, I don’t hold anything inside. I just let it out, and I feel better afterwards.”

Vialli is remarkably comfortable in this interview, even when reflecting on the closeness of death and revealing that he now faces tests every three months to check whether he is still clear of the disease. He nods in acknowledgement when I ask if his past as a footballer prevented him from expressing his emotions before cancer turned his life inside out. “Yes. We portrayed ourselves as tough guys that could deal with anything without showing any weakness. But I now realise the power of vulnerability and that, actually, it can be a powerful tool to get inside people’s hearts. It creates empathy – and empathy is everything. I’m not ashamed of saying we all cry – sometimes because we are scared. In my case I was crying because I was scared of the unknown. I did not know whether I was going to be fine or not. It’s different than if you cry because you’ve lost a match.”

He laughs wryly at the fleeting pain of football. Vialli’s outlook on life has clearly changed over the past three years – while he has endured two separate nine-month spells of chemotherapy which, eventually led to him being declared cancer-free last December.

“This is my personal view,” Vialli says. “But my friends, people who eventually knew about my condition, said: ‘Come on, you’re going to win this fight. You can beat cancer.’ I always felt I didn’t want to fight cancer, because it would be too big and powerful an enemy. I felt this is a journey. It’s about the right therapies and the right doctors. It’s about travelling with an unwanted travel companion until hopefully it gets bored and dies before me.”

Vialli is in a philosophical mood as we discuss his new book, Goals, which features 90 stories about inspirational sportsmen and women who overcame adversity. They range from Jackie Robinson and Jesse Owens to Billie Jean King and Natalie du Toit, Alex Zanardi and Emil Zátopek to LeBron James and Ronda Rousey. They read even more powerfully at a time of great crisis for the world as each story is preceded by a mantra of hope.

Before we read about Zanardi, the motor racing driver who lost both his legs after a terrible crash in 2001, the quote attached to his story reads: “Life is 10% what happens to you and 90% how you react it.” Once he had got used to his prosthetic legs Zanardi returned to Formula One as a test driver and won races in the European Touring Car series. As a Paralympic athlete, Zanardi then won two gold medals at London 2012 before matching the feat four years later in Rio.

“That’s the key mantra,” Vialli says. “It’s all about the way we deal with situations. Alex could’ve gone into a depression, but why focus on the negative? In my situation, I was shocked when I heard I had cancer. But then I thought: ‘I’ve got to make this a journey that helps me grow. I don’t always see it that way, but that’s my aim.”

The book ends with the most compelling story – as Vialli details how two bouts of cancer and chemotherapy affected him. “I found out that pancreatic cancer is one of the worst cancers,” he recalls. “So I was shocked, confused, helpless, hopeless. But it helped that I’d been an athlete. I was used to getting injured and so with cancer I could say: ‘Operation? When? You’re discharging me? When? Then I’m starting chemo? For how long?’ For me it was about setting goals. I also know that nothing is permanent and it will all pass.”

Vialli would learn another brutal truth. Remission can be temporary. His cancer came back in March 2019. “We thought everything was going OK. And then, all of a sudden, you get a temperature. You go for a blood test and they say: ‘Let’s make sure there’s nothing sinister.’ I found out then. It was back.”

Vialli leans closer to the screen. “To be honest,” he says, “I asked myself: ‘Did you really think you were going to get away with cancer that easily?’ The second time was definitely tougher because it’s the cumulative effect. I wasn’t so strong and there was some despair. You’re thinking: ‘Oh my God, this guy is back.’”

Another nine blurring months of chemotherapy passed and, in December 2019, Vialli was given fresh hope. “They call it NED,” he explains. “No evidence of disease. I’m perfectly aware it will take a while before I’m given the all clear. Unfortunately, these things have a tendency to come back. But at the moment I am in a good place. I hope to stay in a good place until I die of old age.”

Football, farce and fascism at the 1936 Olympics

Vialli has anxious days when he worries if the cancer will return. But he spends more time talking about gratitude. “I’ve learned that gratitude is a very powerful emotion. And I’m very grateful to many wonderful people – my wife and family and all the people who have looked after me. They’re not just competent and knowledgeable. They really feel what you’re going through and there’s a great deal of empathy. I’m looked after at the Royal Marsden in Chelsea. It’s an amazing hospital.”

Has it been difficult to maintain such positivity amid Covid-19? “For me it has been hard because I come from Cremona. It probably has the highest death rate in the region. In a way I feel I should be there with my people. I felt so bad reading that people were dying in hospital without their loved ones. It’s a tragedy.

“Staying at home in Chelsea is not a problem. I can work remotely. I can walk to the park. My wife and daughters are here and it’s great to be with them 24/7. In London I only know two people that tested positive. Thank God I have not lost anyone I know in this country. But it’s different in Cremona where there are only 80,000 people. London has six million people. You feel it more in a smaller place.”

What does Vialli think of the Premier League trying to resume next month? “In times of grief, and when you’re going through a difficult situation like this, some psychologists say we should try to do things that give us pleasure without feeling guilty about it. So if football could be a tool to give people some relief then I look forward to its return.

“That said, I can only imagine what the players are feeling. I could advise them about injury or when they fall out with the manager. I can share my experiences with them. But in this situation I wouldn’t know what to tell them. This is unprecedented. If I was still a player, I would probably find it difficult to focus on football because people are still dying.”

Since last October he has worked alongside Roberto Mancini, his former Sampdoria teammate, who now manages Italy. “I have started this new chapter as the head of the Italian national team football delegation. I am so happy I’ve ended up working with my best friend. It feels great to be able to help Roberto and I love trying to inspire the players. My contract runs to the end of the World Cup in Qatar in December 2022. We are carrying on and trying to do as much as possible.”

It seems fitting that Vialli should express his optimism before we say goodbye. “I must think positively,” he says. “I’ve also got to acknowledge when I have some negative thoughts. Acknowledge, separate and challenge them. Yes, I am positive personally. I am also positive about the world. The crisis will pass. What I’d like to see next is that we do not forget these lessons.

“If you look at climate change we have a chance to do something about it. We are now saying health is the most important thing. Great. Why, once the virus is gone, would we go back to living in a place where the air is so polluted? Why don’t we prevent people getting sick and dying from pollution? Surely we should be prepared to give up a little bit of our wealth, our so-called quality of life, for a safer and healthier planet? I feel very strongly about this kind of future.”

Goals: Inspirational Stories to Help Tackle Life’s Challenges by Gianluca Vialli is published by Headline