King of the ring: meet Drew McIntyre, Britain’s larger than life wrestler | Culture

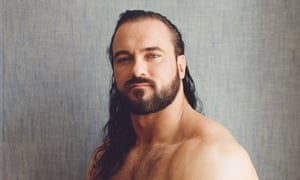

I’m going to try to describe to you the general vibe of Drew McIntyre. Drew McIntyre is a WWE Superstar. Hundreds of millions of people know this, but many others do not. This is the nature of World Wrestling Entertainment Superstardom – and Drew McIntyre is cheerfully resigned to it. He looks heavy, physically, as though it would take six or seven men – normal men – or eight or nine little weaklings like me, to lift him. Drew McIntyre could lift himself up, though, because he has the raw power of an industrial digger. He’s lounging on a sofa in front of me, pre-lockdown, a steak dinner lingering just behind him. And though he is unfailingly polite – thoughtful and sincere with just a crispy little burnt crust of humour round the edges – he does give off the energy, palpably, that he could toss the sofa he’s sitting on up in the air like a baseball and headbutt it through the adjacent wall. He is at once capable of tenderly nuzzling a small puppy and kicking someone’s head through a pub urinal – and that’s what makes him such a captivating superstar. He is hard and soft. He is meat and iron. There’s a lot going on with him.

Earlier this year, McIntyre became the first Briton to win WWE’s Royal Rumble, a wrestling centrepiece event where dozens of the organisation’s storylines converge in a 30-man brawl from which a sole winner emerges. Meanwhile millions of wrestling fans all over the world stay at home watching late into the night, elbow-dropping their furniture in jubilation. Last week, in an empty arena, but viewed by an inflated audience self-isolating at home, he won his title-decider against American wrestling royalty Brock Lesnar in what is the sport’s answer to the Superbowl – WrestleMania 36 – becoming the first Brit ever to do so.

So: Drew McIntyre is at the absolute top of his game. Drew McIntyre is making history right now. Drew McIntyre is a megastar. Drew McIntyre is a superstar. But it almost didn’t happen at all.

We should first briefly confront the reality of wrestling. If you are 10 years old, please don’t read this bit… Yes, it is scripted. And many of the feuds aren’t real (a surprisingly high number of them, however, are). But saying wrestling is inauthentic for not being based on actual frenzied violence is like blasting ballet dancers for not being swans. It zooms out too pragmatically from the centre of the entertainment itself, ignores the high art of pirouetting elbow-first on to someone’s head without killing them in front of an 80,000-strong crowd who you’ve made fall so in love with you that they are deliriously chanting your name. Wrestling, at it’s best, is a Shakespearean good-versus-bad story told through audacious acts of physical violence and microphone shit-talking. And it’s big business. Big, big, astonishingly big, business.

Some facts: according to the Forbes list, WrestleMania is the sixth most valuable sports brand in the world, ahead of the Winter Olympics and the Champions League (the Champions League!). You might not watch it, but heaps of other people do. WWE programming streams to more than 800m households worldwide every year, in 180 countries and in 28 different languages. The Mattel/WWE action figure collaboration is frequently within Mattel’s top-two most sold toys. The various WWE imprints have a combined billion-plus followers on social media. If you still don’t get how big it all is, imagine every football fan on Earth glued to the exact same soap opera.

McIntyre – whose real name is Drew Galloway, which is important to note, because occasionally Galloway answers and occasionally McIntyre does – was 21 when he signed to WWE. (He is now 34.) He was the first Scotsman ever to do so and for a while everything seemed to be going smoothly. He’d become a wrestling nut at 10, and by 15 was pestering his mother to let him train full time; by 17, he’d broken into Scottish independent wrestling and was making his way as a professional. When he was 23, the WWE boss Vince McMahon walked into a packed centre of an arena in Oklahoma and announced that the then semi-unknown McIntyre – baby-faced, smooth-chested, ponytailed and boxed into a big-man suit, looking for all the world like a wedding saxophonist rather than someone who could bench-press a tank – was his “Chosen One”, a future world champion in the making. And then… he wasn’t.

For the duration of his 20s, WWE didn’t know what to do with McIntyre. After an impressive start, he began to struggle for airtime, and then drifted down the ranks. He had all the raw ingredients. At 6ft 5in, he was an athletic marvel, capable of extraordinary acts of in-ring physicality. But wrestling isn’t just about how high you can kick and how convincingly you can take a steel chair to the face. Wrestling is an industry shaped by scriptwriters, tradition and – crucially – the whims of the crowd – and McIntyre managed to slip the notice of all three. By the age of 29 he was partying too much and standing out too little. In 2014, he was finally released from his WWE contract.

McIntyre had started small because he’d had to – 17 years ago, there was barely a British scene to wrestle in. In the summer between sixth form and university, he worked with independent wrestling tours that played the Butlin’s circuit. Travelling five or six days a week, playing nightly to crowds of up to 2,000, he learned the basics by jumping in at the deep end. “It taught me how to play for large audiences who weren’t wrestling fans,” he says now. “You had to learn your audience and how to make them cheer for you as the good guy, or boo you as the bad guy – and then give them a good show. Some would obviously think, ‘Oh, wrestling, I don’t like wrestling.’ But by the end of the night, I knew they’d be on their feet.”

“But how do you do that?” I ask, and McIntyre goes to a wistful, distant place.

“I’m trying to think how to verbalise it… it comes kind of naturally, now. I guess it’s just telling the simplest story you can tell. And the great thing about wrestling, it’s a blank canvas. You’re out there, you’re live – you’re doing your own stunts – and through the match, hopefully you can tell a simple good guy/bad guy story for everyone to understand. Hopefully, the bad guy will get on the crowd and give them something to work with: get them all riled up so they go, ‘man I want someone to punch their face off’. That’s where the good guy comes in. And then you get to play the part of the audience member, punching their face off on their behalf.” You sense that the basics of those early wrestling days – goodies, baddies and Butlin’s – are still in place, now, in the multimillion dollar events McIntyre heads up, the storylines more polished, maybe, the muscles more oiled, but the primal structure underpinning it the same. He is the force for good, Brock Lesnar is the force of evil, and someone is going to punch someone’s face off, and we’re all going to go nuts.

He leans forward, still in the zone.

“And once you get the crowd, you know, into it like that, then there’s nothing more fun than playing with their emotions. When the bad guy is beating the good guy, and they’re like” – he drops his voice in mock fury – “‘God I just want this guy to get up and punch him,’ and when he finally does get a punch in the face, and everybody explodes? That’s the best feeling in the world. And that’s the art to it, I guess.” You may think wrestling is a billion-dollar industry built on muscles, but you’re wrong. It’s built on emotions, too.

After WWE let him go, McIntyre stared into the mirror and figured out what he wanted. His first move was to throw himself back into the independent circuit as hard as he possibly could. (His second move was to grow a gnarly beard.) In that period, it seems as if McIntyre took every non-WWE match on the planet: he won titles under the Insane Championship Wrestling and Evolve brands, as well as domestic belts in Australia, Scotland and Denmark. “When I was fired I told myself: ‘This is on you.’ The only person I had to blame was myself. I said: ‘This was the dream you wanted. You’re gonna have to prove to everybody you are who they thought you were in the beginning.’ And from that moment on, I was in the gym, working as hard as I could. I was travelling as much as I could. Anybody who would have me, I would wrestle for them. Any interview I could do to practise getting better at situations like this, I would do, just to build myself up in every possible area.”

Twice during our interview I ask McIntyre if he ever gets scared, and I get a slightly different response. Watching his fight against another wrestler, Roman Reigns, is genuinely terrifying – watching a 6’3” Aquaman-in-a-vest storm towards the camera in a pitch black arena, let alone being the man he’s about to beat up. I ask McIntyre, who was waiting in the ring to get his ass kicked, whether a pang of genuine fear ever gets to him. “I don’t get scared,” he says, with a bravado tone I recognise from hard lads the world over. “I was face-to-face with Brock Lesnar two weeks ago, and I wasn’t remotely scared. Drew Galloway might get beaten up by Brock Lesnar, but Drew McIntyre believes 100% he’s gonna kick Brock Lesnar’s ass.” But when we talk about his time out of the company, the freefall away from the safety net of his 20s and the uncertainty of his future as a man who pinned everything on one dream and, looming on the edge of 30, having it snatched away from him, there’s a moment where Galloway’s fear peeks out over McIntyre’s mask.

“I know I like to pretend I was confident the whole time and that things were going to work out, but I was very scared, realistically, that things weren’t. And yeah, I just put on a ‘fake it ‘til you make it’ face, I kept a confident face on. But behind closed doors – and we’ve been talking a lot about this recently, my wife and I – she’s been reminding me how I was feeling during that period. I was gone from the company and I was worried and I was anxious and I was angry and… all these different emotions. In my mind, I’m good at blocking out negative memories. In my mind I believed I was right back on the horse and I succeeded instantly, which is not exactly true. And I think the big turning point for everything was breaking my neck one time.”

Ah, uh? What?

In the midst of McIntyre’s WWE wilderness, he was dropped on his head during a match, fracturing two of his vertebrae and confined to a brace for eight weeks. Injuries for wrestlers, though a natural part of the game, can be devastating. If you can’t wrestle, you can’t work. Perilous contracts can fall through while in rehabilitation, long-planned storylines fizzle out and a fickle wrestling crowd forgets who you are. McIntyre’s neck break threatened his comeback. But while he was supposed to be on a sofa letting his neck fuse back together, he was still out drinking, partying and seeing friends. McIntyre’s wife, Kaitlyn Frohnapfel – who he met six months before his WWE release, and who “hates wrestling” – told him in no uncertain terms that he needed to cut out the drinking. “And she was 100% right. I realised I didn’t look as good as I should. I started looking into diet. I started working with a meal-plan company and I cut out the partying. When I came back from the neck break, my physique had changed completely. I looked better than I’d ever looked. And I was back in WWE within three months.”

A cursory read of McIntyre’s story – working hard and getting what he wanted so young, busting the flush, learning the hard way, microwaving a Tupperware of eggs for breakfast because he broke his own neck, getting told to do things then furiously doing them – is, simply, he was a man in his 20s, once. He was young and he was cocky and he needed to be taught that a little humility and a lot of facial hair could transform him completely. I start to ask if, had he had the opportunities he’s fought for now in his early career, he would have made the most of them, and for the first time in our conversation he interrupts me. “I would not have been able to pull them off,” he says. “Maybe physically – in the ring, OK – but I wouldn’t have been able to handle myself.” In a world of manufactured storylines, McIntyre’s genuine life arc is one of the more compelling. Like wrestling, his life is just a simple story studded with exquisite acts of violence. And kicking Brock Lesnar’s face off in an arena last week is just another dose of destiny along the way.

WrestleMania 36 is now on the WWE Network