Lilian Thuram: ‘My classmates judged me because of my skin colour’ | Football

One man in France’s 1998 World Cup-winning squad felt particularly affected by the sense of racial harmony that had descended on the country after that historic triumph. Ever since moving from Guadeloupe as a nine-year‑old, Lilian Thuram was confronted by discrimination. The attitudes he witnessed as a boy shocked him to such an extent that once his career ended, he decided to focus his energy on the fight against racism.

For those few happy weeks after the World Cup, Thuram was delighted to see people in France treated equally regardless of race. “The black-blanc-beur symbol we created was positive and I liked it,” he says of the “black, white, Arab” motto.

“It wasn’t only a reference to the football team, it was about all of society. I’m not naive. I know very well that outside football people aren’t treated the same. They are not allowed to dream about the same things. Depending on your skin colour, depending on your origins, you do not have access to the same opportunities. So this is why I’m very happy that for a period at least there was this recognition.”

I am talking to Thuram at the headquarters of his association in the Odéon district of central Paris. He launched the Fondation Lilian Thuram after quitting his final club, Barcelona, in 2008, with the aim of educating young people on the roots of racism and why it is wrong. France’s most‑capped player now battles racism with the ferocious determination that made him one of the leading defenders of his generation and travels the world for talks at schools, universities and conferences.

Securing a meeting with Thuram has proved difficult and not just because he is extremely busy. Thuram has found himself at the centre of a media storm following an interview he gave to the Italian newspaper Corriere dello Sport. Contacted to discuss the continuing racism in Serie A, he was reflecting on the history of the problem when he said: “It is necessary to have the courage to say that white people believe they are superior.” This sentence upset some of his compatriots and notably prompted the influential football journalist Pierre Ménès to claim: “The real problem in France, in football in any case, is anti-white racism.”

The controversy made Thuram reluctant to accept another interview but a month later he has agreed to meet and seems to be more relaxed. “The fact the subject of racism is being debated more and more is good,” he says. “And if I’m being attacked then it means that in some way my actions are making certain people uncomfortable. They feel in danger, which, again, is a good sign. Don’t forget that Nelson Mandela was accused of being an anti-white racist. Martin Luther King, too.”

The Frenchman does not consider himself to be the next Mandela or King but the number of books on the shelves of his office dedicated to those two historical figures suggest he is deeply inspired by them.

Born in French West Indies, Thuram has been intrigued by the subject of racism ever since his mother moved the family to the greater Paris region in 1981. “What struck me when I arrived was that some of my classmates judged me because of my skin colour. They made me believe my skin colour was inferior to theirs and that being white was better,” he says.

“These were nine-year-old kids. They weren’t born racist but they’d already developed a superiority complex. From that moment I started to ask myself questions: ‘Why are they teasing me? Where does this come from?’ My mother couldn’t provide me with answers. For her this was just the way it was. There are racists and it won’t change.”

Unsatisfied with his mother’s response, Thuram buried himself in books to find a better explanation, studying events that had created this damaging mindset. “Historically, we ranked people. We created hierarchies according to skin colour,” he says. “We educated the white person to think he is dominant over others. Just as we educated men to feel dominant over women. These are intellectual and ideological mechanisms that were constructed in order to exploit other people.”

Thuram speaks in a calm, intelligent manner. His gentle demeanour contrasts with the aggressive way he defended during his playing days. It is also very different to the stereotypical image that some individuals in France have of black people who come from the suburbs. “People like to fantasise,” Thuram says, allowing himself a throaty chuckle. “They like to think the suburbs are full of violent thugs but they’re not. The majority of people are just like me. They try to live well in a calm, peaceful way.”

Raised by his mother, who was a cleaner, in the modest council estate of Les Fougères in Avon, south of Paris, Thuram knows what it is like to struggle on the periphery of French society. Football helped him gain respect in a tough community made up of immigrants from all corners of the globe. “I played with kids from Pakistan, Lebanon, Vietnam, Congo, Algeria … the whole world was there. Football has this great strength of bringing people together and making you feel part of something.”

His first club, Portugais de Fontainebleau, were founded by Portuguese expats but the players hailed from many different cultures. “At the weekends, I became Portuguese,” Thuram says. “Opponents used to insult me by calling me a ‘dirty Portuguese’, which, as a West Indian, I found pretty funny.”

Like many of his peers Thuram spent every spare moment with a ball at his feet. “The best way to be good at something is to do it a lot. When you’re in the suburbs, you play a lot of football. You don’t have access to piano or violin lessons. During the school holidays you don’t go away, you stay at home and you play football all day long. That’s the reason why so many players emerge from these areas.”

Thuram’s world changed when Arsène Wenger brought him to Monaco aged 17. This proved to be the start of a long, trophy-laden career. Yet, for all his success, the spectre of racism never left. At Monaco, despite being a regular in Wenger’s title-chasing team, Thuram would often be refused entry to nightclubs and exclusive restaurants. During the 10 seasons he spent in Italy with Parma and Juventus after leaving Monaco, he heard monkey chants on a regular basis.

It must have been difficult to bear but Thuram had the tools to rise above it. “I was lucky that from a young age I understood the mechanism behind racism,” says the two-times Serie A winner. “So, when I heard the monkey chants, there was no doubt in my mind that the people with the problem were the ones making monkey noises, not me. I didn’t get angry, I tried to understand why they did it.”

Thuram has a burning desire to share his knowledge and, much like his marauding raids forward with Les Bleus, he is difficult to stop when he gets into stride. “Racism stems from a feeling that you are superior to the other person. You think you’re ‘normal’ and they aren’t. It’s the same with homophobia. Heterosexuals were educated to think they are normal and gay people aren’t. Well, we need to explain very nicely to these people that they are not ‘the norm’. There is no norm. I understood that very early and when you understand racism you know you are not the one with a problem.”

When I say that racism in football looks to be escalating because more incidents are being reported, he says the suggestion is naive. But surely the terrible scenes in Bulgaria the week before our interview, when England’s players were racially abused throughout their Euro 2020 qualifier, are evidence the situation has deteriorated?

“People often try to analyse racism through their own country or through their feelings but you have to consider racism on a global scale and take on board the historical depth,” Thuram says. “European societies were built on racism. It has been integrated into the collective subconscious for centuries.”

To illustrate the progress humanity has made, Thuram takes the example of his own family: “My grandfather was born in 1908, 60 years after the abolition of slavery in Guadeloupe. When my mother was born, in 1947, there was segregation in the United States. When I was born, in 1972, there was apartheid in South Africa. In France, state racism ended in the 1960s. If you’re not aware of this deep history, you may think there’s more racism today. But I can tell you there isn’t. There’s far less.”

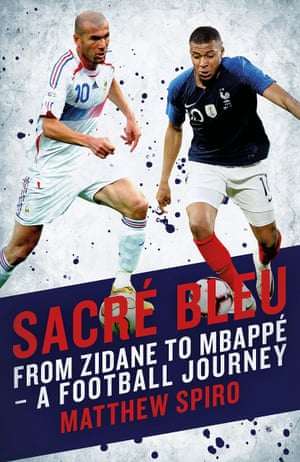

Matthew Spiro’s Sacré Bleu tells the story of France’s turbulent journey from their first World Cup triumph in 1998 to the second 20 years later.

To order a copy for £13.99, visit Biteback Publishing.